Key Highlights

- Discover why efficiency-first supply chains are falling short in 2026, and how hidden structural risks in centralised networks are becoming harder to ignore.

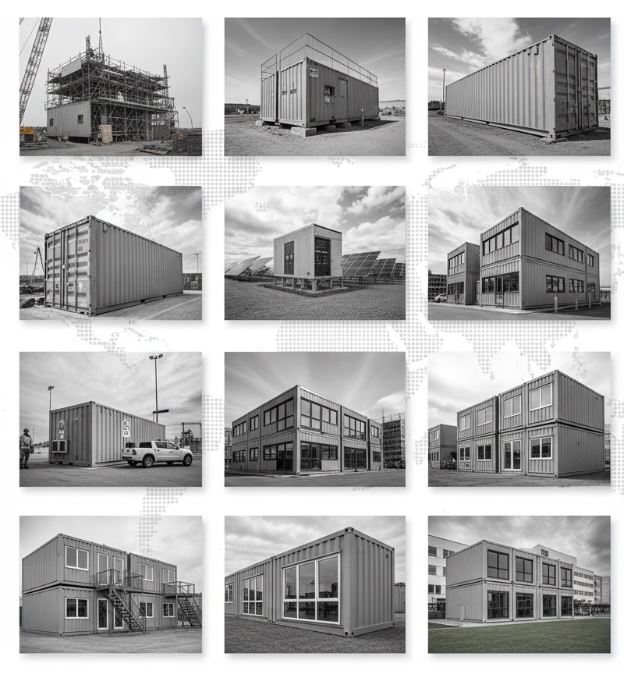

- Modular infrastructure is moving from tactical fix to strategic foundation, enabling logistics networks to adapt without rebuilding from scratch.

- The growing gap between standard containers and engineered modular assets, and why that distinction matters in regulated, remote, or critical environments.

- See how infrastructure strategy is shifting upstream, as large-scale projects and government bodies design for resilience at the manufacturing stage, not just during deployment.

The Risk No One Is Pricing Correctly

In most supply chain discussions, the conversation still circles around the same familiar markers: cost control, throughput speed, and meeting capacity targets. It’s a legacy mindset from decades of optimisation where predictability rewarded scale, and efficiency ruled strategy.

But 2026 looks different. The terrain has shifted, and yet the metrics haven’t. What’s often overlooked in planning models is the single point of failure risk that centralised logistics systems quietly introduce. This isn’t about extreme scenarios or once-in-a-generation events. It’s about how everyday disruptions in one location now ripple further, faster, and with more lasting impact.

When too much of a system is anchored in one geographic area or reliant on one operational node, it becomes fragile by design. Redundancy fades. Buffer zones disappear. And when the unexpected happens — weather, regulation, or access issues — that fragility shows up fast. Not as dramatic collapse, but as delay, constraint, and compounding cost.

This is the risk that doesn’t show up in freight rates or quarterly forecasts. But it’s already shaping the future viability of global logistics.

Centralisation Worked Until It Didn’t

For a long time, the logic behind centralised logistics infrastructure was clear. Consolidating freight through major ports, building mega distribution centres, and working with vertically integrated operators all made sense under the global trade conditions of the past two decades. Scale brought down unit costs. Trade lanes were predictable. Labour was relatively stable.

That model wasn’t flawed. It was built for a different environment.

What’s changed is how frequently disruptions now occur, and how quickly they expose the limits of fixed, centralised systems. Climate volatility, policy shifts, and geopolitical pressure no longer sit in the background. They’re active, overlapping risks that infrastructure must absorb in real time. The systems optimised for volume and cost struggle to adjust when conditions shift midstream.

Where Centralisation Creates Hidden Failure Points

The most serious risks in logistics today aren’t loud or visible. They’re embedded in how systems are structured. Centralisation creates efficiency, but it also introduces failure points that become visible only under pressure.

Geographic choke points like major ports and inland hubs often handle disproportionate volumes. A delay at one node — caused by congestion, weather, or local regulation — doesn’t stay local. It spreads across entire networks.

Single-mode dependency adds another layer. When operations rely heavily on one transport route or provider, there’s limited flexibility when that mode becomes constrained. Fixed infrastructure, meanwhile, can’t easily shift with demand. Warehouses and intermodal terminals are capital-heavy assets that don’t relocate when trade patterns change.

These locked-in systems reduce optionality. And when response decisions depend on large-scale coordination, systems slow down. Centralised networks are rarely designed for fast adaptation under stress. That latency turns small interruptions into system-wide bottlenecks.

The Shift: From Efficiency to Resilience by Design

The most effective supply chain strategies today aren’t throwing out efficiency. They’re redesigning for resilience alongside it.

Instead of planning around throughput alone, organisations are embedding flexibility at the infrastructure level. That means building systems that can absorb disruption without constant rework.

Redundancy is now a strategic choice. Modularity is being built into asset planning. And instead of pushing everything through a handful of major facilities, operators are distributing capacity where it’s needed. This shift makes networks more adaptable and less exposed to single-point failures.

It’s not a rejection of centralised planning. It’s a correction to match new operating conditions. Modular infrastructure plays a key role in making that shift real.

Modular Infrastructure as a De-Centralisation Tool

Modular infrastructure is now a strategic asset class. It allows networks to shift, scale, and replicate functionality across multiple locations without starting from scratch each time.

Engineered modular units can be manufactured off-site, deployed where needed, and relocated as conditions change. That flexibility means infrastructure can support operations without locking them into fixed routes or long-term site commitments.

This is about more than mobility. Modular systems allow duplication of critical functions — from power and water to storage and inspection — across multiple sites. That reduces the risk of total shutdown if one facility goes offline.

Purpose-built assets are already being used in remote environments and time-sensitive deployments. They make it possible to design for adaptability at the infrastructure level, not just in planning documents.

Why Standard Containers Aren’t Enough Anymore

As decentralised infrastructure becomes more common, the demands placed on containers and modular assets are changing. Standard, off-the-shelf units rarely meet the durability, compliance, or integration requirements of industrial-scale projects.

Containers that need to interface with energy systems, mining operations, or regulated industries must perform far beyond basic transport. Long-term environmental exposure, structural load requirements, and compliance obligations require engineered solutions from the outset.

This shift has increased demand for manufacturers that specialise in engineered, large-volume modular infrastructure, rather than standard off-the-shelf equipment. It’s a distinction that separates generic container supply from providers like shippingcontainers.net, which focus on custom-built, compliance-driven container and modular solutions for industrial and government-scale projects.

What This Means for Large-Scale Projects and Governments

For infrastructure planners, government procurement teams, and project leads across mining, energy, or defence, decentralisation is already shaping how developments are scoped and delivered.

Fixed-location builds struggle to meet the needs of dynamic or geographically dispersed operations. Modular infrastructure provides the flexibility to operate across regions without building from scratch each time — while still maintaining compliance and control.

But decentralisation doesn’t happen at the deployment stage. It begins in design. Assets must be engineered with site-specific requirements, compliance frameworks, and long-term service life in mind. Off-site manufacturing allows those standards to be built in from day one.

For operators managing billions in infrastructure, that design-stage alignment matters more than ever.

Designing for a Less Fragile System

Over-centralisation made sense in a stable world. But the same systems that once drove efficiency now pose structural risk.

Organisations that perform best are those building flexibility into the physical infrastructure itself. Modular, engineered solutions allow supply chains to adapt to regional constraints and shifting conditions without constant reinvention.

The question is no longer whether decentralisation is coming. It’s whether infrastructure has been designed to support it.