A group of senior industry figures have analysed the post-Ever Given Suez Canal grounding in a critical reflection of the handling of disrupted supply chains by the industry and they concluded that data-sharing and significant digital collaboration through ports, acting as co-ordinators, can manage supply chain disruptions, benefitting all the stakeholders.

[s2If is_user_logged_in()]Critical incidents such as the week-long blockage of the Suez Canal can disrupt complex supply chains, but when Ever Given was re-floated, on 29 March the race to reach ports and avoid congested berthing and inland connection was on.

A team of experts, including specialists from Maritime Informatics, the Anchor Group and the United Nations body UNCTAD, have concluded that it would be beneficial for all of those involved in the supply chain, from manufacturer to consumer if information was shared and ports acted as co-ordinators to clear logjams.

On 23 March when the container ship Ever Given went off course and blocked the Suez Canal for six days. Various estimates of losses ranging into the dozens of billions of dollars have been floated into the market.

Those numbers are likely inflated compared to the real damage. What is an objective fact is that more than 350 vessels got stuck in the canal and that had real implications. But not all cargo is the same – some cargo is more time sensitive than others.

Data can tell us what cargo is affected by a disruption. But more importantly, data can help us to deal with the ripple effects of incidents to avoid an aggregation of waiting time at the canal and the destination ports.

We, therefore, need to secure enough shared data providing everyone has situational awareness that will enable informed and intelligent decisions. In this article, we elaborate on queue numbers and how such information may support deriving enhanced predictability for reduced waiting time in destination ports in Europe, in Asia and at the East Coast of the United States.

Incidents such as the blocking of the Suez Canal should provide us with the necessary incentives to share data and act collaboratively upon the situational awareness.

The puzzle

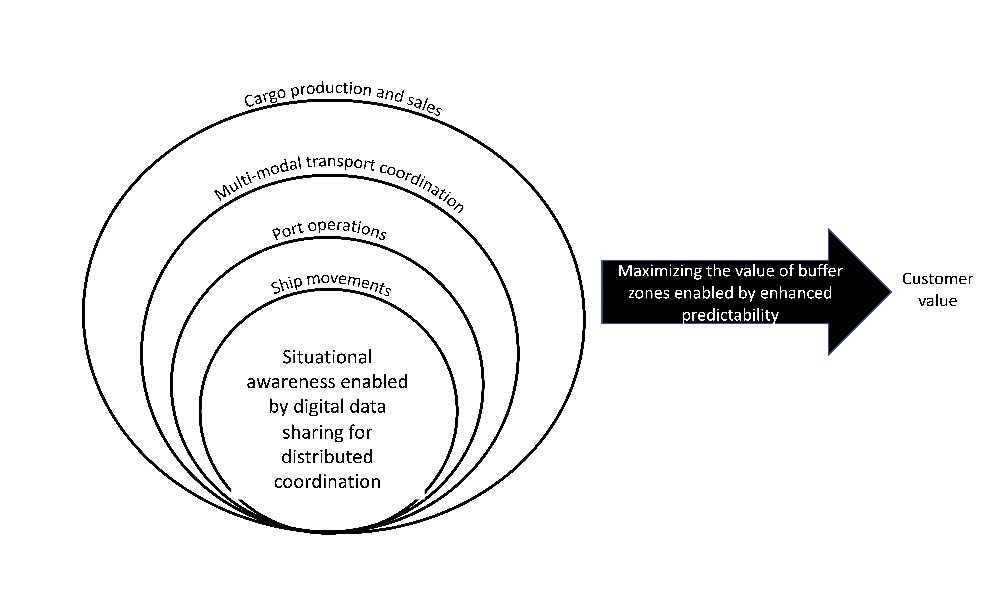

The transport ecosystem encompasses autonomous actors having pieces of a puzzle of common situational awareness that is key to everybody’s co-ordination of their operations. The incident in the Suez Canal reminds us how much an immobilised piece of this puzzle can affect the global supply chain. Therefore, we need to base ourselves on the actual ship movements to assess progress, make plans and address disruptions.

The captain may not be operating the ship in isolation. The shipping company is mainly concerned with securing that ships are moved cost-efficiently and timely over the oceans with high fulfilment of the ship’s carrying capacity. Some argue that the growing sizes of container ships has made it difficult and risky to manoeuvre in narrow passages. For sure, the impact of something going wrong is growing with ship size (see figures 1 and 2).

We have observed that shipping companies, following the Ever Given incident, decided to re-route around Africa. This is estimated to add another US$300 000 to the cost of fuel expanding the distance around 3 000nm or 5 400km for the route between Singapore and Rotterdam.

If vessels speed up, fuel costs and CO2 emissions will rise rapidly. We even noticed vessels making a U-turn on the Mediterranean Sea. Such diversions delay arrivals and consumes more resources. But at least they would predict a better arrival time. This makes such incidents and subsequent decisions a trade-off between capital productivity and energy efficiency for the shipping company.

Ports’ digital progress

When shipping companies share data on plans, progress, and possible disruptions, ports can optimise their use of the infrastructure and resources that are shared among clients. Despite promising initiatives for optimising the ships’ arrival times to the port, the port is just a small piece of the whole transport chain. Whether such initiatives suffice to secure the optimisation of the fleet and port infrastructure remains an unresolved question.

The Suez Canal incident is an opportunity for ports to show their potential as information hubs. They can assume an important role by helping to establish a new level of visibility and collaboration along the chain and among ports. Some experts expect a rush to destination ports because of limited discharging equipment. Reducing potential waiting times in the ports requires organising the arrivals of ships, through pro-actively arranging for some vessels to slow down to avoid congestion, which at the same time conserves fuel. This also allows for better planning the handling equipment in the port and capacity in the hinterland. This requires a higher level of situational awareness through data sharing.

Who benefits

The debates on optimising port operations should be expanded to how the lack of data sharing and collaboration impacts the multimodal transport co-ordinator and the cargo owner and at the end, the ones that buy the cargo, the end-consumer.

Transport co-ordinators, like freight forwarders, are challenged to secure seamless transport end-to-end. Most ports operate on a first come first served basis which makes it impossible for the transport co-ordinator to plan its operations. Ideally, there would be a need for a transport co-ordinator to develop capabilities to re-direct transports based on sequential decision-making, but this does require up-to-date information shared among all actors. Due to lacking predictability of maritime operations both transport co-ordinators and cargo owners introduce buffer zones. Augmented visibility about the journeys of the vessels, waiting times and the available capacity in ports would empower transport co-ordinators to discuss in advance with ports and hinterland carriers the optimal mode and sequence of transport, determined by the cargo owners’ needs.

Beneficial cargo owners can benefit from end-to-end visibility to take risk mitigating actions. Importing companies need to manage their supply chains and their inventories in such a way that can satisfy the time requirements for the end-consumers. They know that disruption can occur at any time and work with the reality of months-long timescales of ocean shipping. While time sensitive cargo is shipped by airfreight or supplied out of well provisioned nearby distribution centres.

The way ahead

Re-engineering practices and securing shared data are prerequisites to optimise maritime flows. A holistic approach, such as the one that is addressed within Maritime Informatics would bring more value to buffer zones and better predictability.

Driven by the Suez Canal blockage, there is a line of ships that passes through the canal based on its arrival time. About 350 ships have been queuing, waiting for the green light for the passage (figure 3). Under normal conditions, the canal manages 55 southbound and northbound passages on a daily basis which in due time decreases the number of ships waiting in line.

Based on the first come first principle it is reasonable to assume that each ship receives a queue number based on when it arrived at the entry point. That would guide our understanding of when a specific ship passes through the canal. A question that remains is whether some ships should be prioritized over other ships, dependent on the type of goods they carry. A marketplace for queue numbers may also be an option to optimise the flow of ships, which may also be a tool to help to reduce port congestion.

The order in line is dependent on how many other ships are waiting to pass. Each of the post blockage 49 southbound heading container vessels stuck in the Mediterranean, and each of the 40 container vessels that were blocked in the Gulf of Suez and that are heading north would have a queue number. The aggregate reflects all ships that are aiming to pass through the canal (figure 4). The place in the queue gives the single operator a foundation for predicting when a specific ship passes the canal, providing grounds for forecasting when it is to arrive at the next port.

By using the real throughput time for the canal combined with data on queue replenishment this would also mean that we would be able to approximately predict which ship would be passing through the canal at what time. This is of substantial value for the actors that would like to predict when the goods will appear at the port and point of destination and consequently being able to plan for the use of buffers and possibly accelerated handling at the port and hinterland transportation or even emergency supply through, for example, airfreight transport.

This analysis also provides us with the capability to follow whether any ships are deviating from the queue system.

In conclusion

In conclusion

Global supply chains will remain vulnerable, exposed to disrupting events. We cannot avoid situations like the Suez Canal blockage. But we can improve our ability to manage their consequences. Situational awareness spanning from the factories to end-consumer can help extract more value from buffer zones.

Depending on the risk level and the risk appetite there will always be an optimum for the size of the buffer zone, and small buffers may not always be the optimal solution given the inherent risks in supply chain networks. Situational awareness helps also to increase customer and consumer satisfaction by a higher level of visibility and predictability, while laying the ground for optimising the chain end-to-end. This requires incentives to share data along the chain, standardised data protocols and the willingness to collaborate as the basis for better alignment, decision-making and integration across different modes.

This is a call to review incentives for data sharing along the global supply chain to achieve higher levels of capital productivity and to better prepare for incidents like the Suez Canal blockage. Only data allows us to pull the puzzle together to manage such situations.

This article is, even more, a call for port collaboration than for data sharing. Data sharing will come over time, but collaboration is needed now. The level of data sharing and collaboration required to smooth the ripple effects resulting from the canal incident, reflects the cultural change that needs to occur as well. If we arrive at predicting when a ship is passing the Suez Canal and arrives at the destination port, we can probably also adapt the same standards, tools and practices to predict congestion at any chokepoint at any port in the world. Which would be a major step towards avoiding or at least significantly reducing waiting time in the maritime industry of tomorrow.

Mikael Lind, Research Institutes of Sweden (RISE) and Chalmers University of Technology,

Wolfgang Lehmacher, Anchor Group, Lars Jensen, SeaIntelligence Consulting,

Torbjörn Rydbergh, Marine Benchmark, Hanane Becha, UN/CEFACT, Luisa Rodriguez, UNCTAD

Read the original article here

[/s2If]

[s2If !is_user_logged_in()]Please login or register to read the rest of the story[/s2If]